[column_content type="two_third"]

Article V of the Constitution provides for two methods of enacting constitutional amendments. Congress may, by a two-thirds vote in each chamber, propose a specific amendment; if at least three-fourths of the states (38 states) ratify it, the Constitution is amended. Alternatively, the states may call on Congress to form a constitutional convention to propose amendments. Congress must act on this call if at least two-thirds of the states (34 states) make the request. The convention would then propose constitutional amendments. Under the Constitution, such amendments would take effect if ratified by at least 38 states.

In part because the only constitutional convention in U.S. history — the one in 1787 that produced the current Constitution — went far beyond its mandate, Congress and the states have never called another one. Every amendment to the Constitution since 1787 has resulted from the first process: Congress has proposed specific amendments to the states, which have ratified them by the necessary three-quarters majority (or turned them down).

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, many states adopted resolutions calling for a constitutional convention to require the federal government to balance its budget every year. From the mid-1980s through 2010, no such new resolutions passed, and about half of the states that had adopted these resolutions rescinded them (in part due to fears that a convention, once called, could propose altering the Constitution in ways that the state resolutions did not envision).

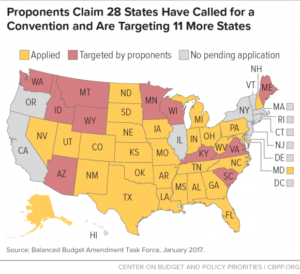

Recently, though, additional states have called for such a convention, reflecting the efforts of a number of conservative advocacy organizations such as ALEC, which in 2011 released a handbook for state legislators that includes model state legislation calling for a constitutional convention.[4] Since 2010, 12 states have adopted such resolutions. According to some proponents of such a convention, a total of 28 states have now adopted resolutions (and not rescinded them). Proponents have targeted another 11 states for action this year and next.[5] (See Figure 1.)

[skill title="White" percent="69" bgcolor="#ff7400"][skill title="Hispanic" percent="32" bgcolor="#ff7400"][skill title="African Am." percent="24" bgcolor="#ff7400"][skill title="Asian" percent="69" bgcolor="#ff7400"][skill title="Native" percent="32" bgcolor="#ff7400"][skill title="Other Am." percent="24" bgcolor="#ff7400"] [/column_content]

Box 1: Balanced Budget Amendment Likely to Harm the Economy

Even if a constitutional convention could be limited to proposing a single amendment requiring the federal government to spend no more than it receives in a given year, such an amendment alone would likely do substantial damage.a It would threaten significant economic harm. It also would raise significant problems for the operation of Social Security and certain other key federal functions.

By requiring a balanced budget every year, no matter the state of the economy, such an amendment would risk tipping weak economies into recession and making recessions longer and deeper, causing very large job losses. Rather than allowing the “automatic stabilizers” of lower tax collections and higher unemployment and other benefits to cushion a weak economy, as they now do automatically, it would force policymakers to cut spending, raise taxes, or both when the economy turns down — the exact opposite of what sound economic policy would advise. Such actions would launch a vicious spiral: budget cuts or tax increases in a recession would cause the economy to contract further, triggering still higher deficits and thereby forcing policymakers to institute additional austerity measures, which in turn, would cause still greater economic contraction.

The private economic forecasting firm Macroeconomic Advisors (MA) found in 2011 that “recessions would be deeper and longer” under a constitutional balanced budget amendment. If such an amendment had been ratified in 2011 and were being enforced for fiscal year 2012, “the effect on the economy would be catastrophic,” MA concluded, and would double the unemployment rate.

Most recent proposals to write a balanced budget requirement into the U.S. Constitution would allow Congress to waive the balanced budget stricture if a supermajority of both chambers voted to do so. However, data showing that the economy is in recession do not become available until months after the economy has begun to weaken and recession has set in. It could take many months before sufficient data are available to convince a congressional supermajority to waive the balanced-budget requirement, if they ever would. In the meantime, substantial economic damage — and much larger job losses — would have resulted from the fiscal austerity measures the balanced-budget mandate would have forced.

Requiring that federal spending in any year be offset by revenues collected in that same year would also cause other problems. Social Security would effectively be prevented from drawing down its reserves from previous years to pay benefits in a later year and, instead, could be forced to cut benefits even if it had ample balances in its trust funds, as it does today. The same would be true for Medicare Part A and for military retirement and civil service retirement programs. Nor could the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation or the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation respond quickly to bank or pension fund failures by using its assets to pay deposit or pension insurance, unless it could do so without causing the budget to slip out of balance.

Proponents of a constitutional balanced budget amendment often argue that states and families must balance their budgets each year and the federal government should do the same. Yet this is a false analogy. While states must balance their operating budgets, they can — and regularly do — borrow for capital projects such as roads, schools, and water treatment plants. And families borrow, as well, such as when they take out mortgages to buy homes or loans to send children to college. In contrast, the proposed constitutional amendment would bar the federal government from borrowing to make worthy investments even if they have substantial future pay-offs. And, as with Social Security, the amendment would prohibit using past savings for current purchases; if a family had to live under its strictures, not only would mortgages be prohibited, but so too would buying a house from years of prior savings.